August 15, 2012 — As NASA has been getting ready its retired space shuttles to set sail for their museum homes, the agency has also been quietly preparing its least known orbiter vehicle to stay in place.

The SAIL — or Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory — is set to become the newest stop on tours of the Johnson Space Center in Houston this fall.

The once fully-functional space shuttle simulator, which was used throughout the 30-year program to develop and test the flight software for each of the 135 missions, was designated an honorary part of the fleet with its own orbiter vehicle (OV) number.

Space shuttle Discovery, which is now on display at the Smithsonian in Virginia, was also referred to by NASA as OV-103. Enterprise, the original shuttle prototype, which is now exhibited at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City, was similiarly OV-101.

Endeavour, which next month will be flown to Los Angeles for the California Science Center, was designated OV-105. And Atlantis, which is scheduled to arrive this November at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida, was OV-104.

The SAIL was designated OV-095. Although it was never space-worthy, from the perspective of its flight computers, the simulated missions that it 'flew' might have just as well been in orbit.

Skeleton of a space shuttle

Filling a couple of floors inside Building 16 at the Johnson Space Center, OV-095 doesn't look like its sister ships.

Although it has a fully-accurate flight deck and is laid out to have a payload bay and aft section, the SAIL's lack of wings, tail — and for that matter, walls — leaves exposed the mock space shuttle's wires, switches, crawl spaces, steep stairs and ledges.

That setup worked well for the more than three decades when the SAIL was an operational laboratory, but was not ideal as a bustling tour stop. NASA needed to make the SAIL safe for visitors while keeping the historical integrity of the facility intact.

The team working to transform the SAIL from a simulation of a space shuttle to a simulation of a facility simulating the space shuttle wanted to maintain the feel of the lab so that the tour felt more like a behind-the-scenes look than a museum display.

"We want to do all we can to honor the great work that was done in this facility," Beth LeBlanc, exhibits manager at the Johnson Space Center, told "JSC Features" writer Hayley Mae Fick.

To achieve that sense of authenticity, the team combed through the facility, and former employees were consulted about even the smallest of items. Take for example, the binder clip that was attached to a long, black string that, to an outsider, might have seemed like nothing more than spare office supplies. It was revealed as an essential part of daily operations to the SAIL team.

Referred to as the "Pony Express," the makeshift clip and string device, which will be on display during the tour, was used to quickly and easily transport paperwork and other small items between the SAIL's upper and lower levels.

The attention to detail is aimed at preserving the scene so well that former SAIL employees will "still feel the same pride for SAIL and be proud to bring their families to see where they used to work," LeBlanc told Fick.

SAILing into shuttle history

The public will be able to choose between two paths to tour the SAIL through the options offered by Space Center Houston, the visitor center for the Johnson Space Center. Tourists will be able to view OV-095 as a stop on the tram tour that is included with general admission or go further in the SAIL on the premium "Level 9" tour.

Entering the SAIL on the first floor of the lab, both types of tours will provide visitors with access to a one-of-a-kind viewing area inside the payload bay of OV-095. Within the naked belly of the mockup, guests will be able to gaze at the space shuttle's extensive wiring system, a maze of thousands of multi-colored wires that gave the simulator — and the real space-flown orbiters — flight.

"It's amazing to think each wire had a specific function," Paul Miller, who is leading the SAIL's transformation from a facility into an exhibit, told Fick.

Level 9 participants will have access inside the middeck and cockpit of OV-095, the latter virtually identical to the other orbiters' flight decks. Each of its switches and LCD displays can activate their corresponding flight controls.

For those on the tram tour, two shuttle program cockpit simulators have been relocated to an empty space outside of the payload bay viewing area to give all visitors to the SAIL the chance to get an up-close look at the controls that the astronauts trained and flew with.

Upstairs on the second floor viewing deck, a section of the floor has been removed so visitors can overlook the cargo bay. From this birds-eye view, guests will be able to get a sense of the massive size of the space shuttle — an otherwise hidden feature of OV-095 provided the way it was built into the building.

Beyond the viewing deck, guests will tour a replica of one of the firing rooms inside Kennedy Space Center's Launch Control Center. Every Apollo and shuttle launch since the unmanned Apollo 4 in 1967 was controlled from an almost identical room in Florida, which just opened as a tour stop at Kennedy Space Center this past June.

Flight simulation logs and other artifacts from the SAIL's days as an operational lab have been scattered across the control center consoles assisting with the illusion that the people who worked there just walked out of the door.

As visitors leave the SAIL for the next stops on their tour, the hope is that they'll walk away with a new-found respect for both the physical hardware and procedures that made the shuttle program possible for the 30-years that it flew.

"While we want our visitors to understand the complexities associated with operating the space shuttle, we also want them to leave the tram stop with the understanding that ground-based simulations are critical to all our missions – past, present, and future," said Michael Kincaid, external relations director at Johnson Space Center. |

|

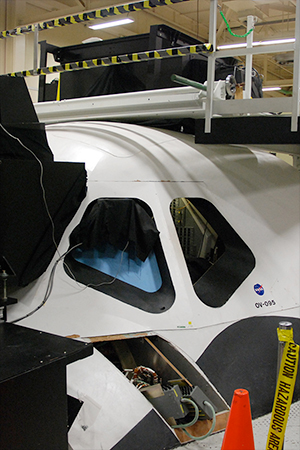

The Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory (SAIL) fills two floors in Building 16 at NASA's Johnson Space Center. (collectSPACE)

Behind these walls and doors lies a space shuttle — the SAIL is a relatively unknown part of space shuttle history. (collectSPACE)

The view from the SAIL's flight deck of its cargo bay reveals the miles of wire that enabled the space shuttle to fly. (collectSPACE)

Avionics boxes and wires lie exposed on the SAIL's middeck for ease of access while configuring flight systems. (collectSPACE)

A replica of a firing room at the Kennedy Space Center's Launch Control Center 'launched' the SAIL's missions. (collectSPACE) |