advertisements advertisements

|

|

A look at Lyndon B. Johnson's space legacy, 50 years after his death

January 22, 2023 — Ask the average person, let alone a space enthusiast, to name the U.S. politician who earned the title "Mr. Space," and Lyndon B. Johnson is not likely to be their first reply.

Before becoming Vice President and President of the United States, Johnson took a leadership role in shaping the country's space policy in the opening weeks of the Space Age. As the majority leader in the Senate, he helped form the response to the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik, the world's first satellite, in 1957.

It "put him up-front in the public eye as being 'Mr. Space,' an image he held for many years as the one politician who was truly interested in the space program and its implications for the future of the United States and its place in the future development of mankind," Glen Wilson, who served as a staff assistant to Johnson in the Senate, wrote in a 1992 essay on the origins of the legislation that created NASA.

Now, decades later, the nation may have forgotten the impact Johnson had in steering the course of the U.S. space program well beyond the time he was in office and even the years he was alive. The decisions that he made, including championing the Outer Space Treaty and Apollo program, continue to influence today's activities in space.

"There's no question that LBJ's legacy relating to space is under appreciated and undervalued as we look at the history of space exploration," said Mark Updegrove, former director of the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and president and CEO of the LBJ Foundation, in an interview.

Updegrove spoke with collectSPACE about the contributions LBJ made to space exploration policy and how the president's legacy is perceived today, half a century after the President's death on Jan. 22, 1973. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): For those not familiar, what was it that first gave Johnson the reputation of being "Mr. Space" in the public eye?

Mark Updegrove: It was Lyndon Johnson really who was the chief catalyst for the creation of NASA in 1958, after Sputnik had been launched by the Soviet Union in 1957. He worked very closely with Dwight Eisenhower to ensure the United States would respond in a responsible way to the Soviets' first foray into space and the fear that they would dominate space, giving them a major leg up technologically at a time when the Cold War defined geopolitics. Lyndon Johnson, as the all powerful majority leader, was very much at the forefront of creating a space program that would respond to the Soviets' efforts in space.

cS: Was Johnson's interest in space strictly about gaining a political advantage?

Updegrove: I don't know that it was political advantage. I think there was a deep concern that the Soviets would gain a technological advantage and be able to put weapons in the sky. Again, this is at a time when MAD — Mutual Assured Destruction — was an acronym that everybody knew because there was a deep fear of a nuclear exchange. In fact, the bulk of the American people by the time that John F. Kennedy took the presidency believed that there would be a nuclear exchange in their lifetimes.

So, we were deeply concerned about any advantage that the Soviets might have over the United States. In fact, John F. Kennedy earned the presidency principally by instilling fears in America that there was a missile gap between the Soviet Union and the United States. The Soviets putting up Sputnik and showing that they could actually launch something into space, showed that they were, at least in the minds of some, technologically superior and could use that to their military advantage.

cS: Is there evidence that LBJ also had a personal interest in space exploration? Did he see it as a scientific endeavor as well?

Updegrove: I don't know if that was part of his thinking.

While we were concerned about technological superiority, we also wanted to show the world the can do nature of who we are as Americans. I think that probably intrigued Lyndon Johnson more so than the scientific advantages, although there are things in the Great Society that showed he had a real interest in science, as well as the arts and all different aspects of American life.

But to my mind, one of the principal reasons that he did this was to show the world that we had the technological know how to do this and the can do spirit. That was one of the highest accolades that Lyndon Johnson could pay to anyone, to call you "a can do man" or "a can do woman." He embodied that himself. He was able to do things, which is the very reason that John F. Kennedy tasked him with figuring out what our space efforts would look like going forward after the initial creation of NASA.

cS: Some historians believe that if Kennedy had not been assassinated, we would not have landed on the moon in 1969. Kennedy had tried three times to curtail the program and had been unsuccessful in his efforts to engage the Soviets in a joint mission. White House audio recordings suggest his interest in supporting NASA's activities were guided by geopolitics.

With that in mind, what was it that drove Johnson's interest to continue Apollo after Kennedy's death, given congressional and public scrutiny at the time? Why did he feel it was so important to achieve the moon landing?

Updegrove: I wrote a book on John F. Kennedy called "Incomparable Grace" that came out last year and I'm not sure I share that assessment. I know that Kennedy talked to [NASA Administrator] James Webb and talked about pulling the plug on the program if if it wasn't something that we could do. But I do think he was also intrigued by the adventure of it all.

First and foremost, it was a measure to equalize things in the Cold War. For the very reasons I suggested that Lyndon Johnson supported the creation of NASA and our efforts in space for political reasons, so too did John F Kennedy. But I also think if you hear about Kennedy's conversations that he had with the Apollo astronauts, I think he was truly intrigued with the adventure of space as well. There's evidence of that and it very much fits in with the Kennedy image and the Kennedy persona in my view.

Lyndon Johnson, I think, was deeply committed to NASA from the beginning. It bears mentioning that I'm not sure that we would have reached the moon by the end of the decade but for the Apollo 1 fire that happened in 1967, killing three astronauts. LBJ's presidency shows, particularly as it relates to civil rights, that he let no good crisis go to waste. And I think with the Apollo 1 fire, he saw that the projects had been mismanaged, shortcuts have been taken to meet deadlines and work was unintentionally compromised. It was an opportunity to reevaluate the program when the fire occurred and to make NASA better.

So without that, as soon as the Apollo 1 fire came in the wake of the Gemini missions, I'm not sure we would have achieved our goal of sending a man to the moon by the end of the decade.

cS: Beyond the creation of NASA and advancing the moon landing, the other major space-related effort by LBJ was the Outer Space Treaty. How important to him was it to make sure that space exploration was done in a peaceful manner, not just by the U.S., but by all space-faring countries around the world?

Updegrove: [The treaty] is one of the unheralded triumphs of the Johnson administration. I'll use LBJ's own words: "This treaty means that the moon and our sister planets will serve only the purposes of peace and not of war. … It means that astronauts and cosmonauts will meet someday on the surface of the moon as brothers and not as warriors."

We saw the plaque that the Apollo 11 astronauts and President Nixon signed when the Apollo 11 mission went to the moon in July of 1969, "We come in peace for all mankind." I'm not sure there would have been that kind of tenor without the Soviet Union agreeing, and other nations agreeing, to the Outer Space Treaty, ensuring that that we did not put weapons into space. That rendered the space race far less dangerous. It made it this test of the human spirit, not an opportunity to put weapons in the sky, as well as on planet Earth.

cS: Do you know if LBJ had some sense of how long lasting the Outer Space Treaty would be, given how it continues to serve as the basis for all of space law today?

Updegrove: I don't know, but I think he would be extraordinarily pleased that it's still binding. That and the Nuclear Non Proliferation Treaty are things that have stood the test of time. They have stood in place for coming on 60 years now. It is remarkable. It's amazing how they shaped the future at a time when we were advancing so rapidly technologically. He'd be very pleased that they still are in place today and still have teeth.

cS: Had Johnson not withdrawn from seeking a second (full) term as president and had he prevailed over Nixon, how do you think the space program would be different today? Do you think he would have pushed to continue Apollo further, or do you think he would have pursued the space shuttle like Nixon did, having arrived at the same conclusion based on the economy at the time?

Updegrove: My guess is that he would have seen the eroding public support for the very expensive space program. This is a man who had enormous ambitions domestically, and I think he probably would have seen the expense of NASA as compromising some of the laws that he might put on the books in order to enhance the Great Society. That is my guess.

He was a political pragmatist and I think he would have bowed to the wishes of the American people having accomplished the goal of putting a man onto the moon, not just once but on six different missions. Twelve American men walked on the face of the moon. That's a pretty big accomplishment. I think the pragmatist, in the political sense, and the fiscally prudent Lyndon Johnson would have would have capitulated and said, "I hear the American people and we will curtail our efforts in time, but we'll aim for other space efforts down the line."

cS: The six moon landings were indeed a big achievement. Why do you think LBJ does not get more credit for them, at least in terms of the public associating him with accomplishment?

Updegrove: One of the reasons that Lyndon Johnson doesn't get credit is because he wasn't president when the major milestones in space happened. He wasn't there when the Mercury missions occurred, putting us in space for the first time. We did have the spacewalk during the Gemini missions, but let's face it, the real life milestone in space exploration was the Apollo 11 moon landing. Apollo 8 was big at the time when Lyndon Johnson was still president at the end of 1968 when that mission occurred and it was huge in the history of space, but it was really superseded by the landing of men on the moon with the Apollo 11 mission.

Richard Nixon gets as much credit for space exploration by virtue of being president when Apollo 11 went up as Lyndon Johnson does. So that is bit of misfortune for Lyndon Johnson in terms of the timing of his presidency.

cS: Do you think that there's anything that can be done today to correct that record, to make sure the public understands that Johnson was critical to everything that Kennedy and Nixon is associated with in terms of space?

Updegrove: I think if the public knew what LBJ was doing behind the scenes, they would understand that it was really a co-effort. Ultimately, the two presidents by far who contributed the most to our efforts in space are John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

It was John F. Kennedy who boldly said we'll put a man on the moon before the end of the decade at a time when the Soviet Union had huge advantages in the space race. At that point, they were far ahead of us. But the reason he did it is because of a memo from his vice president who told him that we can do it by the end of the decade. Lyndon Johnson assures John F, Kennedy in his memo that it can be done and it is with that assurance that Kennedy goes forward with that incredibly bold statement.

cS: Where do you personally rank LBJ's space legacy as compared to his other accomplishments?

Updegrove: That's a really good question. I think that legacy of Lyndon Johnson is a three legged stool.

First and foremost, you have the laws of the Great Society, which I alluded to earlier, and they are breathtakingly far reaching. But in particular, it's those laws that relate to civil rights that make it so distinctive because there had been no great progress since Reconstruction on the issue of civil rights and it's Lyndon Johnson that makes us true to our most sacred creed, which is that all men are created equal. That's the most basic tenet of American egalitarianism. And it doesn't happen until the flurry of laws that are signed by Lyndon Johnson, most notably the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act. Those are vitally important in the in the history of our nation.

Second, you've got to put the tragedy of Vietnam. It is Lyndon Johnson who is primarily responsible for the escalation of the war. The buck stops in large measure with our Commander in Chief and it was on his watch that we escalated the war.

But then the third leg of that stool, importantly, is being a catalyst as Senate Majority Leader for the creation of NASA and being a major supporter of that program, not only when he was in the Senate, but as vice president and president. I'm not sure that there will be a bigger story in the 20th century than us leaving this celestial body and going to another for the first time in the history of the world. That's a pretty big accomplishment and Lyndon Johnson deserves as much credit for that as I believe any politician.

cS: How do you think he would rank those three himself?

Updegrove: I don't know. He was he was enormously proud of what he accomplished in space and looked with pride upon those missions, Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 in particular. But where he would rank it in terms of his legacy, I can't say.

I think he would probably want it to come ahead of Vietnam, but he would also understand that Vietnam was bound to be a vitally important part of his legacy. |

|

Six months after leaving the White House, Lyndon B. Johnson becomes the first President of the United States to attend a launch, the liftoff of the Apollo 11 mission on July 16, 1969. (NASA)

As the Senate Majority Leader, Lyndon Johnson — seen here with President Dwight Eisenhower in 1955 — led the effort to respond to the Soviet launch of Sputnik, the first satellite. (Library of Congress)

Senator Lyndon Johnson met with the original Mercury 7 astronauts in May 1959, a month after their selection. (National Archives)

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed an amendment to the Space Act, naming Vice President Lyndon Johnson the head of the National Aeronautics and Space Council. (National Archives)

Gemini 4 commander Jim McDivitt (at center) and command pilot Edward White (at left) present President Lyndon B. Johnson with a framed photo of White's historic spacewalk. (National Archives)

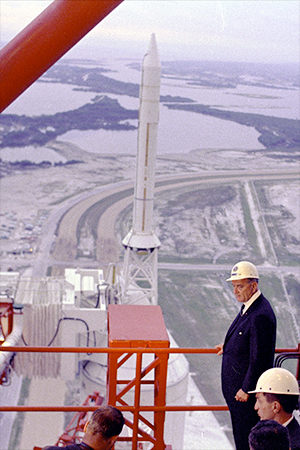

In September 1966, Lyndon Johnson toured Cape Kennedy (today, Kennedy Space Center), including ascending the launch umbilical tower at Pad 39A to view the Saturn V 500-F facilities demonstrator, as pictured. (National Archives)

President Lyndon B. Johnson met with representatives from the UK and Soviet Union to sign the Outer Space Treaty on Jan. 17, 1967. Johnson pushed for and helped author the pact. (National Archives)

President Lyndon Johnson was at Arlington National Cemetery for the funerals for Apollo 1 astronauts Roger Chaffee and Virgil "Gus" Grissom on Jan. 31, 1967. (National Archives)

NASA officials and Apollo 7 astronauts Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham sign friendship stones at the LBJ Ranch at the invitation of Lyndon Johnson in 1968. (National Archives)

Apollo 8 astronaut Jim Lovell presents President Lyndon Johnson with an inscribed photo of "Earthrise" in 1969. (National Archives) |

President Lyndon B. Johnson addresses NASA employees at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas on March 1, 1968. The center would be renamed for Johnson on Feb. 19, 1973, a month after the former president died. (National Archives) |

|

© 1999-2025 collectSPACE. All rights reserved.

|

|

|

|